Imagine picking apples from a tree: the more apples you pick, the higher the chance of encountering a bad one. This analogy illustrates that not all people or situations are inherently bad or against you, but sometimes you simply run into a “bad apple.” In today’s episode, we explore how this concept relates to the amygdala, the part of the brain that regulates our fear response, and how it can influence our perception and reaction to anxiety-inducing situations.

Table of Contents

Introduction to the Amygdala

The Role of the Amygdala in Anxiety

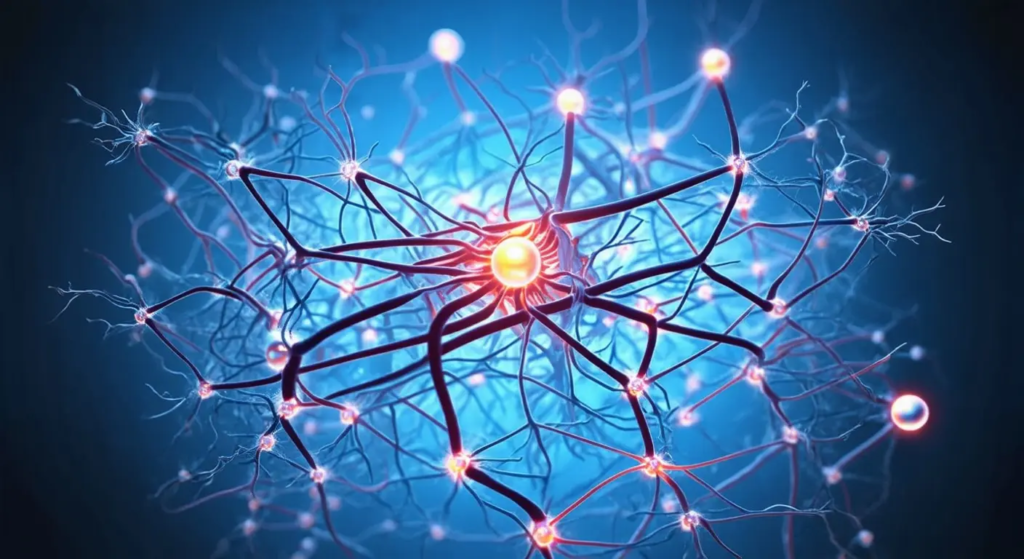

The amygdala, a tiny part of your brain within what we call the limbic system or the emotional brain, regulates your fight or flight response. This small but powerful structure plays a crucial role in how we experience fear and anxiety.1

Automatic Fear Responses

Many times, anxiety and panic aren’t conscious processes. People often don’t consciously think their way into these emotional states; they just suddenly feel anxious. This is because the amygdala can trigger an automatic fear response without our conscious input. You might find yourself in a situation where you’re suddenly overwhelmed with fear or anxiety, seemingly out of nowhere. This reaction is your amygdala at work, responding to perceived threats based on past experiences and stored memories.2

Unconscious Processes

Understanding what’s happening at an unconscious level is crucial for managing these feelings. The amygdala operates largely outside of our conscious awareness, processing emotional reactions quickly and efficiently. This speed is a survival mechanism, designed to protect us from immediate danger. However, in the context of modern life, it can sometimes cause disproportionate responses to non-threatening situations.3

Implications for Health Anxiety

In the case of health anxiety, the amygdala might overreact to physical sensations or medical information, interpreting them as signs of serious illness. This can lead to a cycle of anxiety, where the fear of illness itself becomes a source of distress. Recognizing that these responses are driven by the amygdala can help in developing strategies to calm the brain and reduce anxiety. Techniques such as mindfulness, cognitive behavioral therapy, and relaxation exercises can be effective in retraining the brain to respond more calmly and rationally to perceived threats.

Understanding the amygdala’s role in anxiety provides a foundation for addressing and managing these automatic fear responses. By becoming more aware of how your brain processes fear, you can begin to take steps toward reducing its impact on your life.

The Negativity Bias

Understanding the Negativity Bias

The first thing you need to understand about your amygdala and anxiety is the negativity bias. The amygdala looks for bad news. Around 70% of the amygdala’s cells are organized around negative stimuli, which means there’s a high potential for you to unconsciously associate anything as a threat. This built-in negativity bias is a survival mechanism that helped our ancestors respond quickly to dangers. However, in the modern world, this can lead to heightened anxiety and fear in situations that aren’t truly threatening.4

Everyday Examples of Negativity Bias

For instance, a balanced individual would see a pencil simply as a writing tool. However, an anxious person might see it as a potential weapon and worry about the unlikely scenario of being stabbed by it. Similarly, someone who had a bad experience with water might become overly cautious and anxious around water, fearing another incident even if there’s no real danger present.

The Impact on Daily Life

The amygdala’s tendency to focus on negative stimuli means that it can attach a sense of threat to almost anything. This can lead to a constant state of anxiety where you perceive potential dangers everywhere, even in mundane objects and situations. Understanding this bias is crucial because it helps you realize that not all perceived threats are real, and many are simply a result of your brain’s natural inclination to focus on the negative.5

By acknowledging the amygdala’s role in this process, you can begin to challenge and reframe these automatic negative thoughts. This awareness is the first step towards reducing unnecessary anxiety and fostering a more balanced perspective.

Real-life Examples

The Pencil Example

Imagine looking at a pencil. The balanced part of your mind would think, “This is for writing.” However, if you are in a heightened state of anxiety, you might think, “What if someone stabs me with this pencil?” This is an example of how the amygdala can distort reality by focusing on potential threats, even when they are highly unlikely.

The Water Example

Similarly, a past bad experience with water could make you overly cautious about drinking it. Suppose you had an accident at the beach involving water. Now, every time you see a glass of water, your amygdala might trigger a fear response, associating the water with danger. This bias means that we often see threats where there are none, based on past negative experiences.

Generalizing Threats

This tendency to generalize threats can extend to many areas of life. For example, if you had a negative experience with one person, you might start to believe that all people are untrustworthy or dangerous. The amygdala’s role in these generalizations is significant, as it links current experiences to past negative ones, creating a loop of anxiety and fear.

By recognizing these patterns, you can begin to question and challenge the validity of these fears, helping to break the cycle of anxiety. Understanding how the amygdala contributes to these reactions is a crucial step in managing and reducing health anxiety.

The Role of Memory

Amygdala and the Hippocampus

When the amygdala finds bad news, it works with the hippocampus, which is responsible for long-term memory, to create a memory for the context of that bad news. This collaboration is crucial for survival, as it allows us to remember and avoid potential dangers. When a threat is perceived, stress hormones are activated, preparing the body to respond. The memory system then stores this bad news for immediate retrieval if anything similar occurs in the future.6

Impact of Stress Hormones

The activation of stress hormones ensures that the body is ready to respond to threats quickly. These hormones heighten alertness and prepare the body for action, but they also reinforce the memory of the threat, making it more likely to be remembered in the future. This process explains why our reactions today are often based on past experiences, especially those from childhood. Early experiences are particularly influential because they occur when the brain is still developing, setting patterns for how we respond to stress and anxiety throughout life.7

Generalizing from Bad Experiences

This mechanism can lead to generalizations. For example, if you had one bad experience with a person, you might generalize that all people are bad and start avoiding social interactions to prevent triggering anxiety. The amygdala doesn’t differentiate between different people or situations; it links similar experiences to protect you from perceived threats.

Real-world Implications

Imagine you’re criticized by someone at work. If your amygdala and hippocampus store this as a significant threat, you might start to believe that all coworkers are critical or unfriendly. This generalization can lead to social withdrawal and increased anxiety in professional settings. Similarly, a single traumatic event, such as a car accident, can result in a generalized fear of driving or even being near cars.8

By recognizing this pattern, you can begin to challenge these generalized beliefs. Understanding that these responses are based on your brain’s attempt to protect you can help you take steps to reframe and reduce these fears. Cognitive-behavioral strategies, mindfulness practices, and gradual exposure to feared situations can be effective in breaking the cycle of anxiety and improving your quality of life.

Understanding the interplay between the amygdala and the hippocampus highlights the importance of addressing past experiences to manage present anxiety. By doing so, you can begin to dismantle unhelpful generalizations and develop a more nuanced and accurate view of the world around you.

Managing the Amygdala Responses

Holding Positive Experiences

Positive experiences need to be held in awareness for a significant amount of time and repeated consistently to move from short to long-term memory storage. Unfortunately, negative experiences tend to be stored much more easily, which can contribute to the persistence of anxiety and fear. This means that consciously cultivating positive experiences is essential for managing anxiety.9

Overcoming Negativity Bias

To counteract the amygdala’s negativity bias, you must consciously work on feeling better, thinking above your emotional reactions, and acting above your emotional reactions consistently. This requires intentional effort and practice, but over time, it can help reprogram your brain’s response to perceived threats. By focusing on positive experiences and deliberately challenging negative thoughts, you can begin to reshape your brain’s automatic responses.

Reprogramming Your Responses

You need to guide your amygdala rather than letting it guide you. Accepting the role of the amygdala in generating fear responses is the first step towards managing anxiety. By understanding how the amygdala operates and its tendency to focus on negative stimuli, you can begin to take proactive steps to lead it in a more positive direction.

Acceptance and Leadership

Accepting the role of the amygdala doesn’t mean resigning yourself to a life of anxiety. Instead, it means acknowledging its influence and taking control of your responses. By leading your amygdala rather than being led by it, you can free yourself from the grip of anxiety and thrive both internally and externally.

Techniques for Reprogramming

Techniques such as mindfulness meditation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and relaxation exercises can help you reprogram your responses and develop a healthier relationship with your amygdala. By consistently practicing these techniques, you can learn to regulate your emotions more effectively and reduce the frequency and intensity of anxiety symptoms.

Conclusion

The amygdala is a powerful part of the brain that significantly impacts our anxiety levels. By understanding its functions and biases, we can begin to manage our responses more effectively. Remember, the key to overcoming anxiety lies in consistent, conscious efforts to reframe our experiences and guide our amygdala towards positive associations.

If you have any other questions about any of my recovery programs around anxiety, head on over to https://dennissimsek.com/anxiety-program and check out my programs. Remember, you are more than anxiety. I’ll see you in the next episode. Bye-bye.

If you are enjoying this podcast, please subscribe and give it a positive rate and review. Don’t forget to check out the original Anxiety Guy podcast on iTunes with new episodes airing every Monday morning, Pacific Standard Time. Remember, you are more than anxiety. See you in the next episode.

Sources

- THE ROLE OF THE AMYGDALA IN FEAR AND ANXIETY https://emotion.wisc.edu ↩︎

- Individual differences in anxiety and automatic amygdala response to fearful faces: A replication and extension of Etkin et al. (2004) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov ↩︎

- Amygdala-driven apnea and the chemoreceptive origin of anxiety https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov ↩︎

- Not all emotions are created equal: The negativity bias in social-emotional development https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov ↩︎

- Implicit Negativity Bias Leads to Greater Loss Aversion and Learning during Decision-Making https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov ↩︎

- Amygdala and hippocampal subregions mediate outcomes following trauma during typical development: Evidence from high-resolution structural MRI https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov ↩︎

- Neurobiological Programming of Early Life Stress: Functional Development of Amygdala-Prefrontal Circuitry and Vulnerability for Stress-Related Psychopathology https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ ↩︎

- Neurobiological Programming of Early Life Stress: Functional Development of Amygdala-Prefrontal Circuitry and Vulnerability for Stress-Related Psychopathology https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ ↩︎

- Brief learning induces a memory bias for arousing-negative words: an fMRI study in high and low trait anxious persons https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov ↩︎